. @PaddyVipond. #TortureReport. #torture. #warcrimes. #ICC4USA.

Guilt and Responsibility: Lessons from the Holocaust

If you shoot a person dead, you are rightly held accountable for their death. What happens if you press a button to initiate a machine that shoots a person, are you just as responsible? How accountable are you, if you are in the room at the same time that the process is occurring and you choose to do nothing to stop it? Where does the responsibility for the death of a person begin and end?

In the late 1930’s and the early 1940’s, Nazi Germany and its allies and satellite states embarked on a process of human extermination. The event we know as the Holocaust saw the most depraved and barbaric actions human beings are able to inflict upon each other. Though exact figures are impossible to decide upon, approximately 11 million people were killed for being considered sub-human. Among them were the deaths of over six million Jews, as Adolf Hitler and the Nazis looked to eradicate the Jewish people from the face of the earth.

In camps set up around central and eastern Europe, victims were transported to their deaths. The names of these camps will forever be etched in the history of the human race. A constant reminder of the cruelty that we as a species are capable of: Treblinka, Belzec, Buchenwald, Chelmno, Sobibor and Auchwitz are places that are considered as manifestations of pure evil. It is important to remember though, that evil did not create such suffering and destruction: humans did.

When the Second World War ended, those serving under Hitler were able to remove their uniforms and return to society. (A problematic situation which Brad Pitt’s character attempted to overcome in the movie Inglourious Basterds by carving a swastika into the head of Nazi military personnel.) The wartime period had been nothing but a bad dream to them, and as they washed their hands of their country’s Nazi past, so too they washed their hands of the events they had participated in. One man who did this was Oskar Groening.

Once the war had ended with the surrender of Germany, Groening spent a few years in Britain, before returning home in an attempt to lead a normal life. For years Groening did not fully divulge the role he played in the war. Though he admitted to being in theSchutzstaffel (SS), he chose to omit certain parts of his service. Decades after the war, whilst Groening was leading a comfortable middle class life he encountered a group of people who denied the Holocaust had ever happened. Upon reading their pamphlets and leaflets, he replied, “I saw everything, the gas chambers, the cremations, the selection process. One and a half million Jews were murdered in Auschwitz. I was there.”

Oskar Groening was a former employee of Auschwitz, who at this time is under investigation in Germany and has recently been charged with 300,000 counts of accessory to murder. After enrolling in the SS and working as a bookkeeper for a year, he was transferred to Auswchitz where he became the accountant of the extermination camp. His primary role was to sort and count the money taken from the Jews who were transported there, before sending it to Berlin. Groening very rapidly learnt of the camps actions, but after several months accepted his role within it and referred to his job as “mundane”.

Recently I discussed Groening’s case with two of my housemates, and was astonished to hear that they both believed the man to be innocent of any wrong doing. In what rapidly escalated into quite a heated debate my housemates insisted that Groening was not guilty, and was not responsible in any way for the deaths of the 300,000 Jews. The reasons they gave were that he never actually killed any Jews himself, and that he was in a system that forced obedience and eliminated choice.

I was told that calling this man guilty was ridiculous. He had no choice in the role he played, as the brutality and forceful nature of the Nazi military meant that he had to follow orders no matter what. Groening also never directly participated in any of the killings of the Jews. He did not unload them from the trains — though he was present, he did not beat them with batons or rifles, he did not force them into the “showers”, and he did not handle the poisonous substances which would bring about their excruciating deaths. As a man that caused no direct deaths, he could not possibly be guilty.

Furthermore, if Groening was to be considered guilty then so must those soldiers who rounded up the Jews to be transported, so must the train drivers, and so must the UK government who knew about the massacres yet turned away Jewish refugees regardless. As early as 1941 the Allied forces knew of the Nazi plans to exterminate large numbers of Jewish people, and yet the governments and military decided to do nothing. My housemates argued that if Groening was guilty, so too was almost everyone else.

I agreed somewhat with the point regarding the guilt of the UK government, and upon stating that to my housemates it was again labelled as ridiculous. But I don’t think that it is. And I believe that if both my housemates were to really fully comprehend the issue, then they would be forced to come to the same conclusion as I have.

It is interesting to note that both the housemates that I had this discussion with are vegetarian. I had asked them why they did not eat animals, and they both said that it was because they did not want an animal to die in order for them to survive. Eating meat was a redundant activity as you do not need it to sustain human life, and if you were to eat meat then you were responsible for the death of that animal. I completely agree with them on this point, and it is precisely that reason as to why I am a vegetarian, but through their explanation of why they do not eat meat, the hypocrisy and lack of coherent thinking is evident.

How can eating meat make someone responsible for the death of an animal, but working for the SS at Auschwitz not make someone guilty of the death of Jews? After all one does not directly kill the animal, one does not take the knife and slit its throat, but through a process of indirect association eating meat is intrinsically linked to animals being slaughtered. You cannot eat meat without an animal dying, and you cannot work as an accountant at an extermination camp without humans being gassed.

Groening openly admitted that he saw himself as “a small cog in the gears”, but it is small cogs that allow the machine to continue to function. The farmers that rear cattle for slaughter are cogs, the truck drivers that transport cattle are cogs also, so too are the customers that purchase meat from their local supermarket. If we truly think that the only people guilty of an animals death are the ones that slit its throat in the slaughterhouse, then we are deluding ourselves. Everyone in the process plays a role, and every role comes with a measure of guilt and responsibility.

One of my housemates presented me with a hypothetical scenario whereby a police officer was ordered not to interfere with a burglary on a house. The police officer’s superior directly stated that they must stand and watch, and allow it to happen. I was then asked if this police officer was guilty of the burglary, to which I responded that in part, of course they were. Once again my housemates were outraged. They believed that as the police officer was following orders not to interfere, and not to interrupt, they were absolved of guilt or responsibility.

On the topic of following orders and having no opportunity to go against your superiors, I was reminded of the well-known experiment by Stanley Milgram where ordinary people are encouraged by a man in a white lab coat to give lethal electric shocks to strangers. The experiment highlighted the role that an authority figure has on what actions we take, and how far we are willing to take things if we simply follow orders. This was presented to me as proof that the SS man, Groening, was not guilty of anything, as not only did he never physically and directly kill anyone, but he was also forced into conducting the actions that he did.

Using the Milgram experiment to absolve someone from guilt is incorrect, and it is clear the German legal system sees that, hence why Groening is still being charged with a crime. Those who were giving the electric shocks in the Milgram experiment would have faced similar charges had the shocks been genuine. Though the orders came from above, they played the role of actor and without them no action would have occurred. Milgram’s experiment itself never intended to focus on the innocence or guilt of those conducting the shocks, the experiment was conducted in order to measure obedience. From the findings of the experiment, it is clear that humans are obedient subjects when faced with an authority figure, it does not say that we are innocent subjects when faced with an authority figure. Quite obviously you can be both obedient and guilty.

For me, Groening is guilty. He is a man who not only volunteered to enter the SS, a group who were renowned as being ideologically loyal and driven to carry out Hitler’s wishes, but he is also a man that made very little attempt to escape the situation he found himself in. Perhaps more concerned with his career, he continued to count the money of dead Jews day after day, despite knowing of their fate in the gas chambers. He was even witness to some of the murders stating that he once saw a child “lying on the ramp, wrapped in rags. A mother had left it behind, perhaps because she knew that women with infants were sent to the gas chambers immediately. [He] saw another SS soldier grab the baby by the legs. The crying had bothered him. He smashed the baby’s head against the iron side of a truck until it was silent.”

My housemates would argue that Groening was unable to leave such an institution, that he had no choice but to stay there, and that perhaps he was a victim of circumstance. It is strange then that in 1944 Groening had a transfer application accepted, and was moved away from the camp. In Daniel Goldhagen’s excellent history of the Holocaust, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, he highlights numerous instances were Nazi officers or military personnel transferred from positions, refused to follow orders, or fled their posts as they did not agree with the work being done. To assume that the Nazi regime allowed for no freedom of choice for its participants and followers, is to make a tremendous error in thinking.

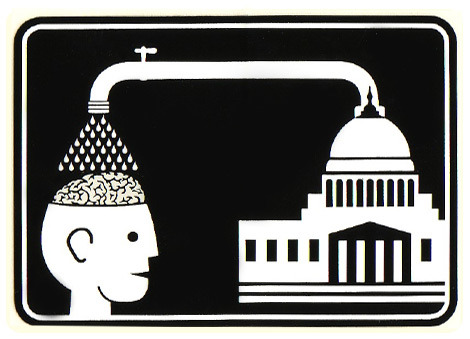

As I mentioned earlier, the machine cannot work unless all the cogs are moving and working in unison. The situation that all individuals of the modern era have found themselves in is that we are all cogs in the machine of the state, whether we like it or not. Therefore the greatest problem for Anarchists and other anti-government groups and movements is that by simply existing, by paying taxes and buying products, we are complicit, to a degree, in the actions of the government that “represents” us.

This is why the well-known phrase “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention” resonates so much with me. Not only does this phrase state that you should be angry about what the government is doing to you and your friends, but it also states that you should be angry about what actions the government are conducting in your name.

Through our taxes, and through the representative democratic system — which gives legitimacy to those that have been voted in — governments are able to illegally invade other nations, kidnap, torture and imprison foreign peoples, privatise previously public-owned institutions, and support, and defend, tyrants, dictators and human rights abusers around the world.

Though we are all but minuscule cogs in the machine that is the modern state, we are cogs nonetheless. Without us the machine cannot function, but with us it is able to commit atrocities across the globe. To deny that we are in no way responsible for the actions in Afghanistan, Iraq or Guantanamo Bay is to take the same stance as Oskar Groening. Though he is perhaps more guilty for the deaths of the 300,000 Jews than we are for the inmates being held in Cuba, it would be incorrect to say that we are entirely innocent.